Brownout again!

This article explores the current state of energy access in Eastern Visayas, focusing on common issues like brownouts, high electricity prices, and potential solutions for a sustainable future. By examining the roles of government, local communities, and the impact of environmental and economic factors, we aim to shed light on the region’s energy landscape and possible paths forward.

Table of Contents

Frequent Brownouts and Blackouts

What is a Brownout? What is a Blackout?

Electricity is the lifeblood of modern society, powering everything from household appliances to critical infrastructure. However, its distribution is not always stable or consistent, leading to phenomena known as brownouts and blackouts, which disrupt this essential service.

Brownouts are reductions in voltage in the electrical power supply. They are not total power losses but are instead temporary, partial outages that can still significantly affect electrical devices. Brownouts can cause lights to dim, air conditioners to lose efficiency, and electronic devices to function improperly. They are often implemented intentionally by electric utilities to avoid a complete power outage by reducing the load on the power system, especially during peak demand times or emergencies. However, they can also occur unintentionally when the power supply fails to meet the demand unexpectedly.

Blackouts, on the other hand, refer to the complete interruption of power supply to an area. They can be localized to a specific neighborhood or widespread, affecting entire cities or regions. Blackouts can result from various causes, including severe weather events, equipment failures, or system overloads, and unlike brownouts, they leave consumers without any electrical power until the issue is resolved.

In 2001, together with the Republic Act No. 9136, also known as the “Electric Power Industry Reform Act of 2001,” that mandated the creation of the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC), the Philippine Distribution Code was established.

"WHEREAS, the Distribution Code shall provide for the rules, requirements, procedures, and standards that will ensure the safe, reliable, secured and efficient operation, maintenance, and development of the distribution systems in the Philippines;"

On the matter of Voltage Variations it states, that undervoltage is present at a voltage below 198V and overvoltage above 242V and that "The Distributor shall ensure that no Undervoltage or Overvoltage is present at the Connection Point of any User during normal operating conditions."

Therefore, we can quantify, that a brownout is present, if the voltage is below 198V or above 242V.

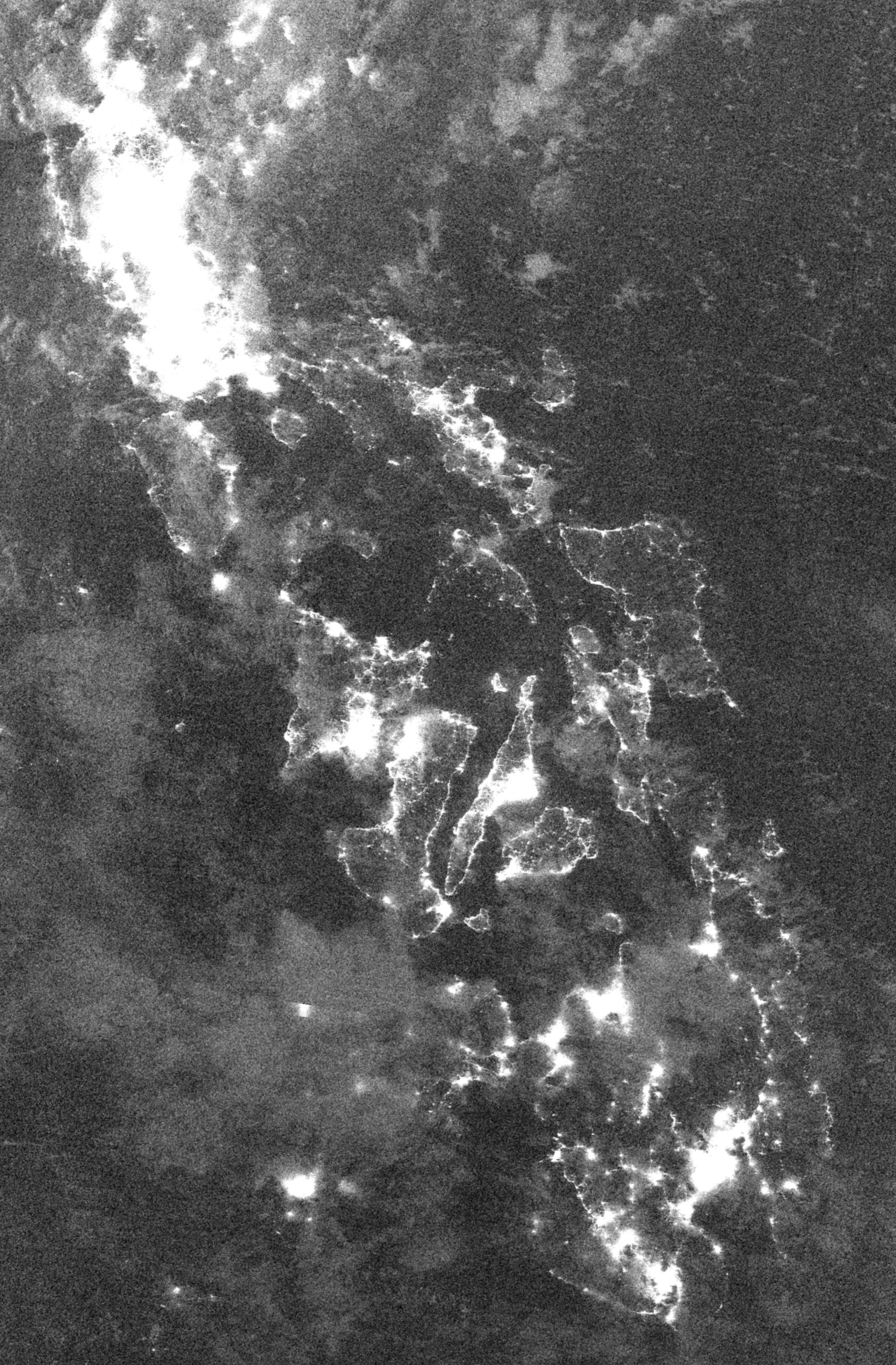

In the last three months, we have been monitoring voltage levels from the grid at a town proper in Eastern Samar, located about 30 meters from the nearest transformer. This area has relatively low electricity demand, with few high-power devices in use.

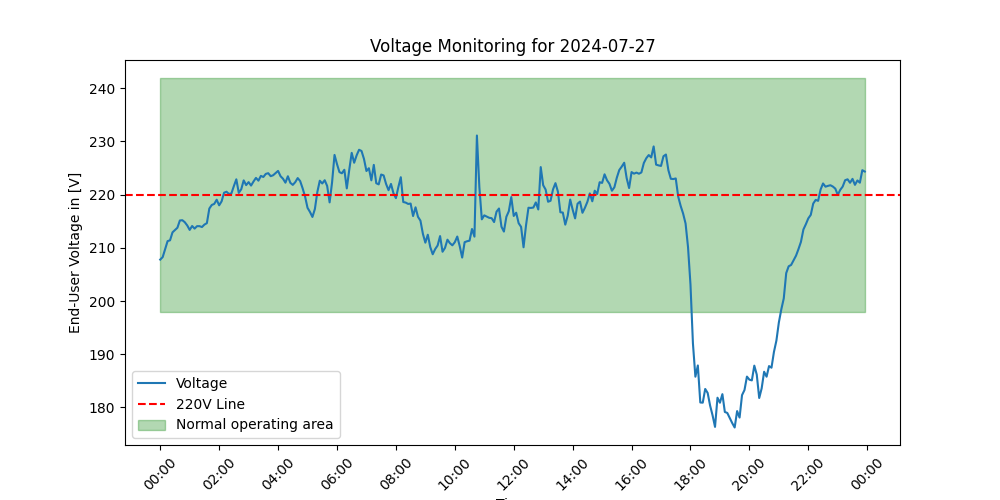

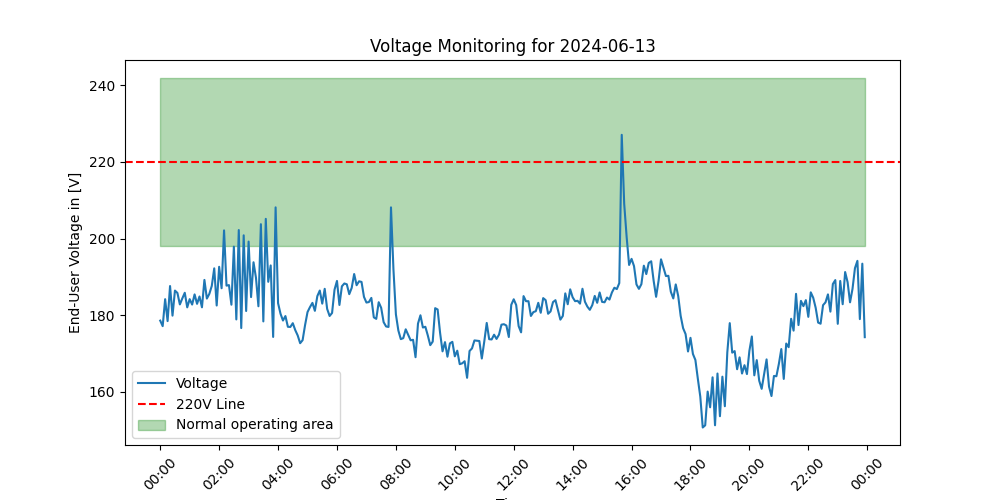

The recorded data reveal significant day-to-day variations in voltage levels. For instance, on July 27, the voltage remained mostly within an acceptable range throughout the day. However, on June 13, the area experienced nearly continuous undervoltage conditions, severely affecting daily activities.

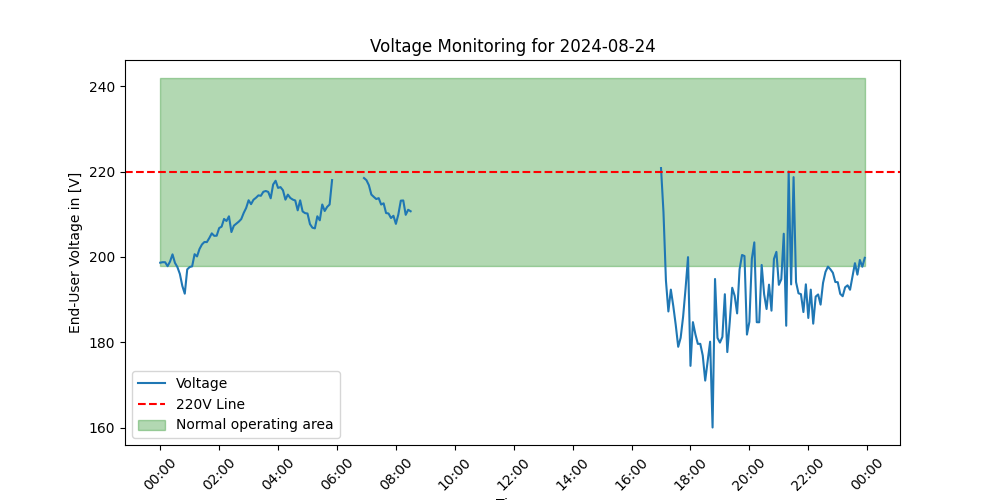

On August 24, a notable blackout lasting almost seven hours was recorded, highlighting the instability of the local power supply. A consistent pattern observed across various days shows a marked voltage drop between 17:00 and 18:00, coinciding with sunset and a surge in electricity usage as residents turn on lights and other appliances.

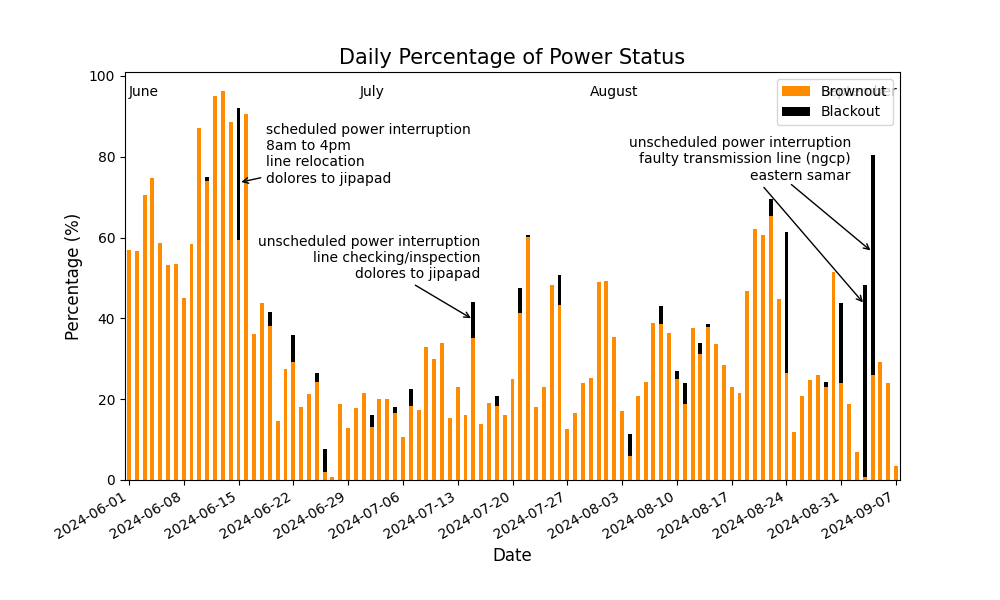

Over the past three months, our data reveals that brownouts are a persistent issue in Eastern Samar, occurring daily. While June experienced particularly severe conditions with brownouts affecting over 50% of each day, improvements were observed in the following months. By July and August, the frequency of brownouts decreased, averaging around 20% of the day.

Blackouts, though less frequent than brownouts, occurred at least weekly. These power outages varied in duration—sometimes lasting only an hour or two, but at other times extending much longer. Notably, a continuous 24-hour blackout impacted the region on the 3rd and 4th of September, highlighting ongoing challenges in maintaining stable power.

Over the past three months, Eastern Samar experienced 14 scheduled and 8 unscheduled power interruptions, each lasting from 30 minutes to an entire day. These outages were primarily due to maintenance and equipment replacement efforts, such as updating insulators and transformers, and general system enhancements to boost reliability. Additionally, vegetation line clearing was routinely carried out to prevent outages caused by encroaching foliage or fallen branches. Emergency repairs were also necessary for sudden infrastructure damages from weather impacts or accidents, and system upgrades were implemented, including the installation of new transformers and the enhancement of existing facilities to improve capacity and service quality.

The Complexities of Electricity Pricing

Exploring the Factors Behind High and Fluctuating Electricity Rates in the Philippines

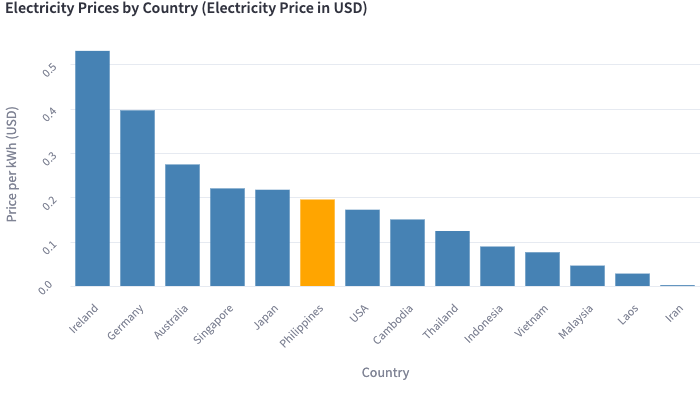

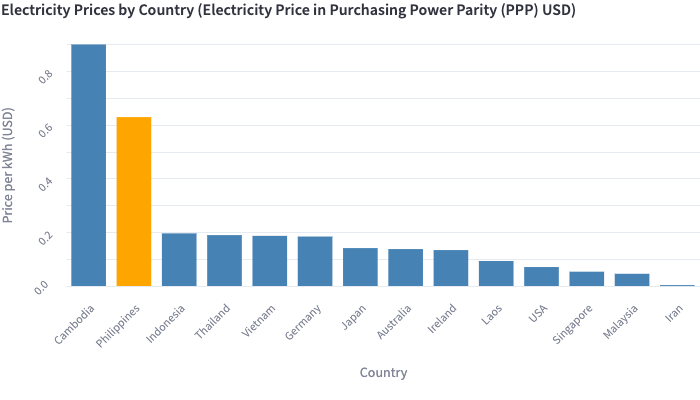

International comparison

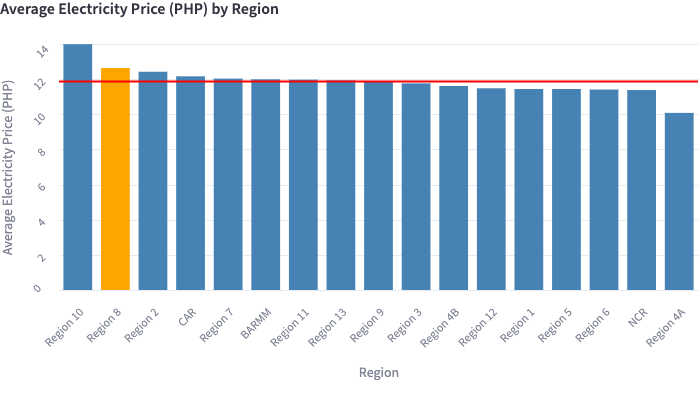

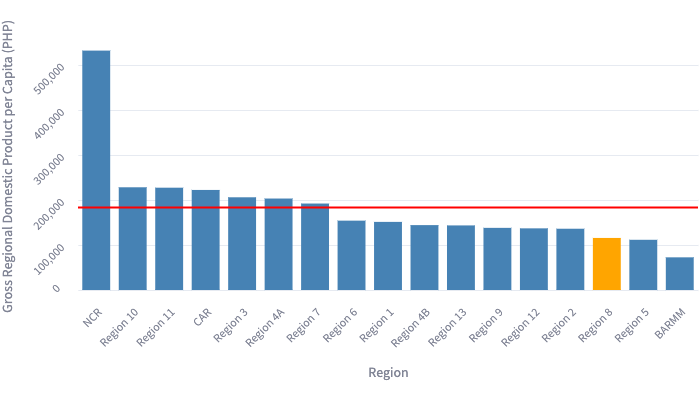

National differences

The source

The breakdown of electricity rates in the Philippines reveals that residential consumers bear a significant portion of the cost burden. Generation charges consistently make up the largest component, accounting for around 60% of the total rate across all user categories. Transmission and distribution charges vary slightly, with residential users often paying higher rates. System loss charges, which add about 10% to the total cost, further increase rates due to inefficiencies in the distribution network. Supply and metering charges introduce additional distinctions: while residential users face a variable supply charge, non-residential customers typically incur a fixed monthly fee, increasing their overall costs. Taxes, particularly VAT, also play a crucial role, adding approximately 4-5% on top of the generation charge, which disproportionately impacts residential users. As a result, residential consumers end up paying the highest effective rate per kWh, often 5-10% higher than commercial and industrial rates. This pricing structure highlights the significant financial impact on households, with high generation costs, taxes, and inefficiencies driving up rates, while minimal subsidies provide limited relief to vulnerable groups.

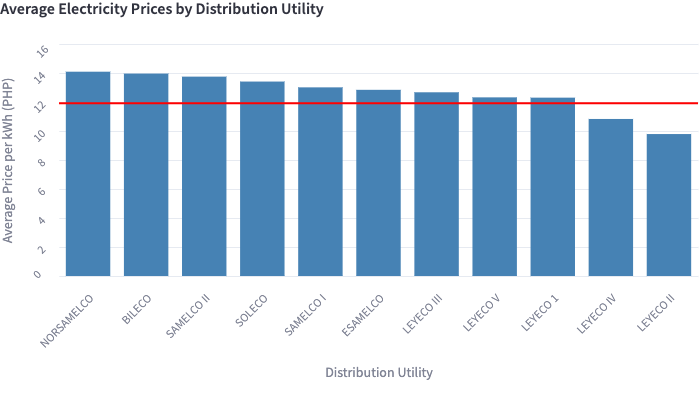

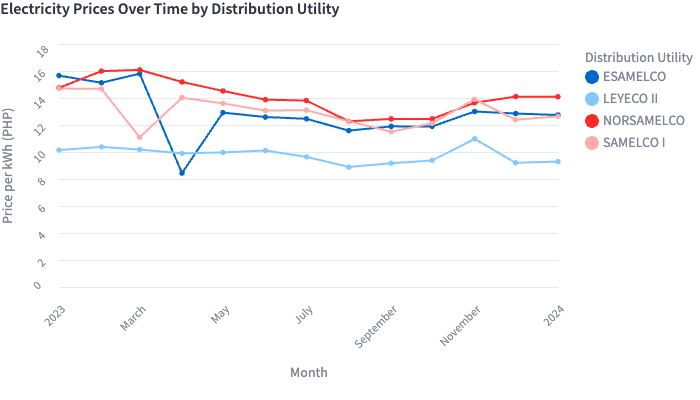

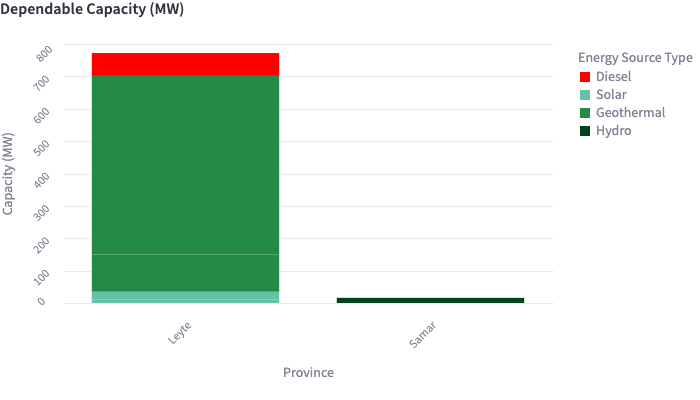

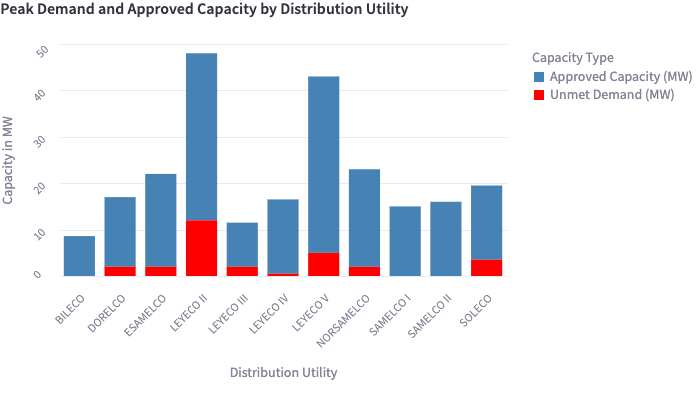

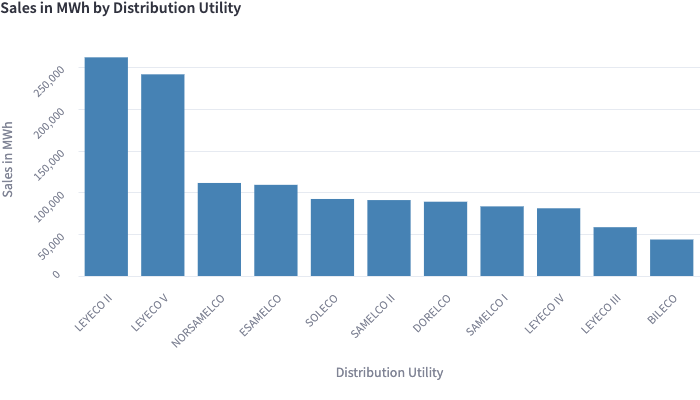

Price volatility in Eastern Visayas’ electricity market is largely driven by the region's dependency on coal and diesel power sources. Despite having significant renewable energy production within the region, many distribution utilities (DUs) are bound by contracts with coal and diesel power plants. As a result, global price fluctuations for these non-renewable fuels directly affect generation costs, leading to unpredictable and often rising electricity prices for consumers. This reliance on fossil fuels not only hampers price stability but also undermines the region’s renewable potential, as the substantial production of local renewable energy remains underutilized in mitigating cost variations.

Infrastructure costs in Eastern Visayas contribute significantly to the region’s energy price instability and are a key factor behind recurring brownouts and blackouts. Funding constraints limit the development and maintenance of robust distribution networks, while operational costs continue to rise, largely due to aging infrastructure and the high expense of disaster-proofing energy systems. Although investments in resilient infrastructure are essential to mitigate the impact of frequent typhoons, these costs further strain electricity prices, amplifying volatility. Without sufficient funding for reliable infrastructure, the region remains vulnerable to both service interruptions and fluctuating energy costs, burdening consumers with inconsistent supply and unpredictable rates.

The 2023 Regional Development Report (RDR) from NEDA highlights a transformative year for Eastern Visayas in renewable energy, power transmission, and electrification expansion, with several key infrastructure initiatives underway. Among the milestones, the San Bernardino Ocean Energy Project on Capul Island, Northern Samar, stands out as the country’s and Southeast Asia's first tidal power plant. Developed by Energies PH, Inc., the project began its engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) phase in January 2023 after a decade of planning. Once operational, the plant will provide 1 MW of clean energy, replacing diesel generators for Capul Island's 15,000 residents.

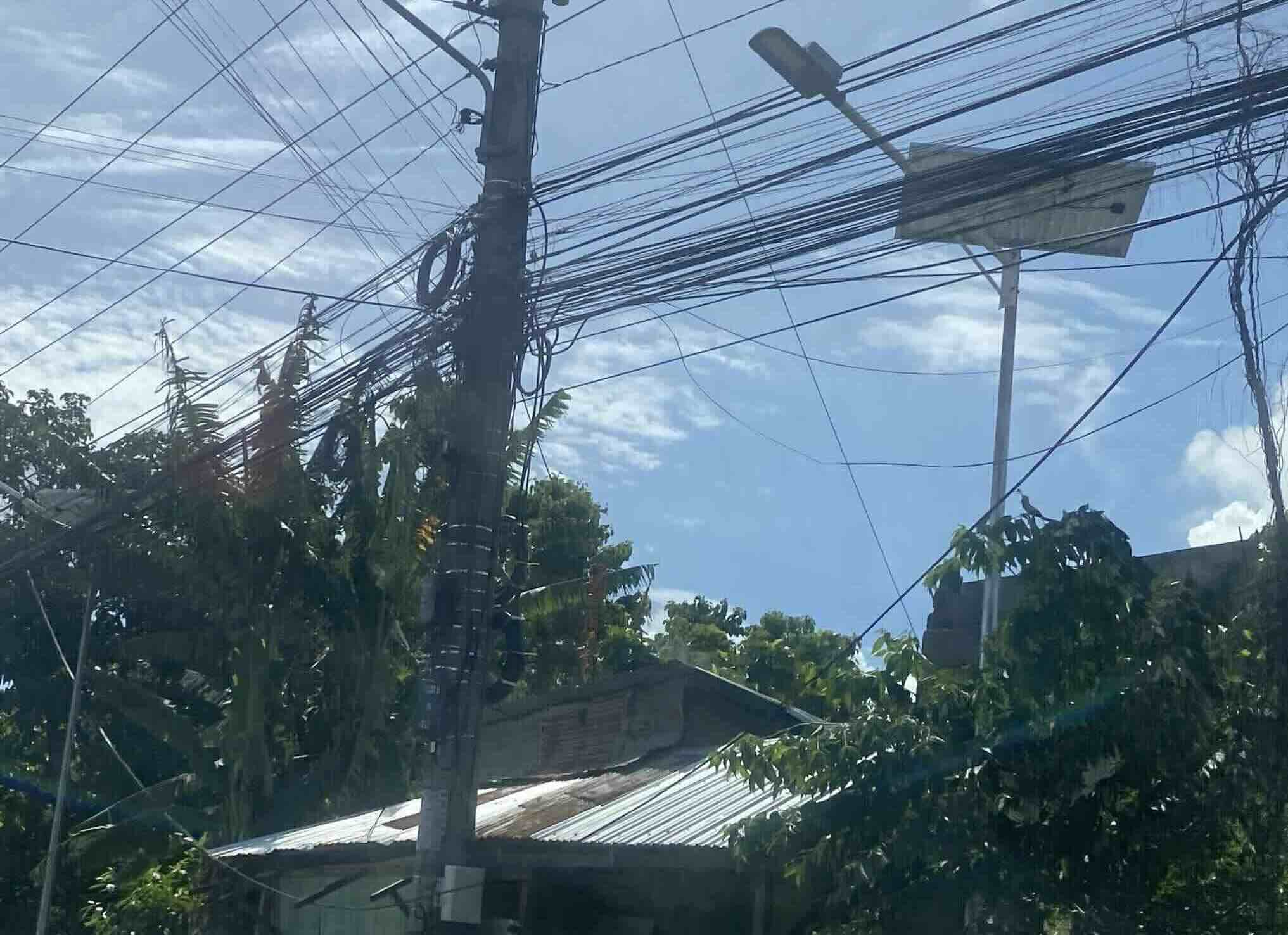

In Region 8, numerous solar street lights have been installed along national highways over the past two years, particularly in rural stretches where electricity access is unreliable or even inaccessible. For these remote areas, solar lighting provides a practical solution. However, in urban settings like Tacloban City, where electricity is readily available along the roads, solar street lights seem less sensible. The picture on the right shows one such solar light beside a neglected electricity pole tangled with messy wires. Instead of installing solar lights here, it would make more sense to repair and upgrade these existing poles and install grid-connected lights, a more cost-effective and logical choice. Furthermore, solar street lights in Region 8 depend on sunlight, making them vulnerable to outages during cloudy days, low-pressure systems, or tropical storms, when they may not operate as expected. For cities with a functional grid, enhancing grid-connected lighting would be a more reliable approach.

In terms of power transmission, the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines (NGCP) made strides with the PhP52 billion Mindanao-Visayas Interconnection Project (MVIP), activated in April 2023. This project, featuring a 184-kilometer high-voltage direct current submarine line with a 450 MW capacity, links the power grids of Mindanao and Visayas, promoting a One Grid system across the country. This connection reduces interruptions and facilitates energy sharing between regions, allowing surplus power from Mindanao to support Eastern Visayas.

Further upgrades to the regional transmission network are underway with NGCP’s Visayas Substation Upgrading Project 1, involving the installation of 1.5 MVA transformers at substations in Tabango, Leyte; Maasin City, Southern Leyte; and Calbayog City, Samar. An additional phase, Project 2, scheduled for 2024-2025, aims to enhance system reliability and meet increasing demand.

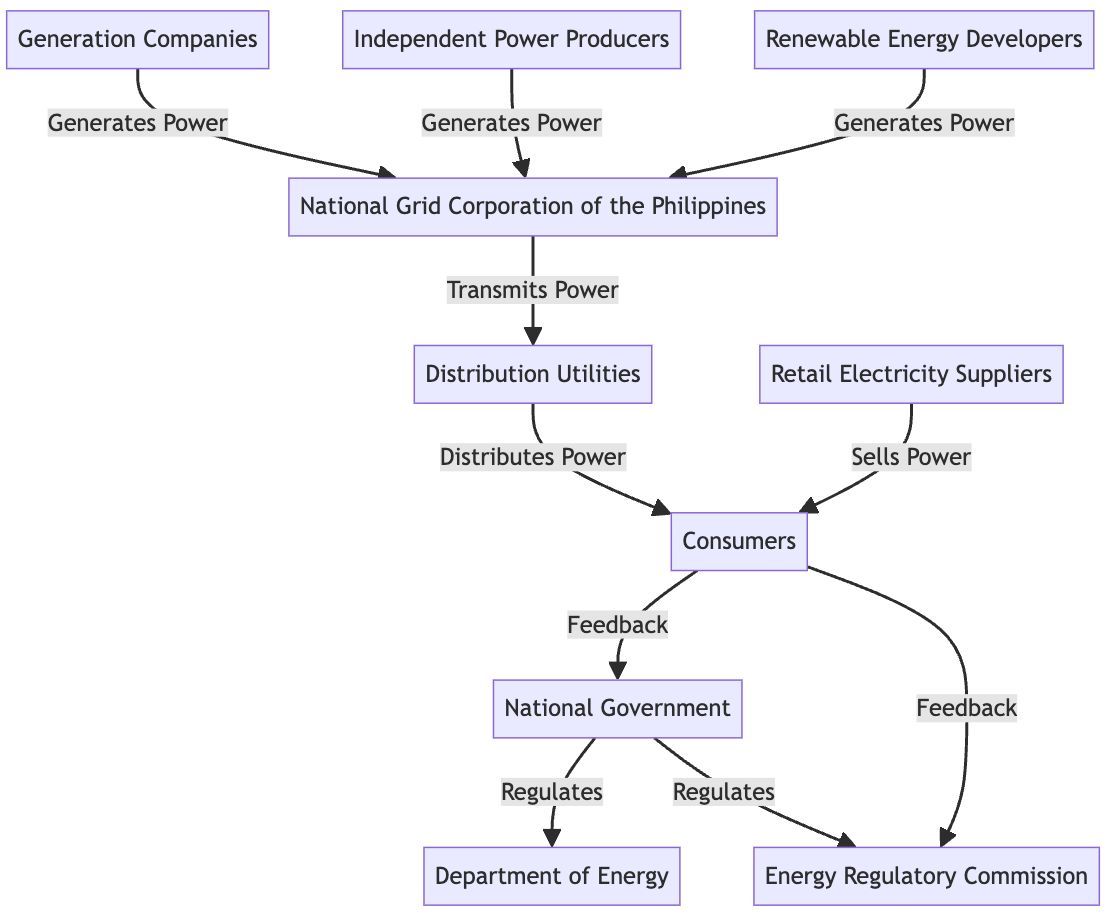

Stakeholders

- National Government:

- Department of Energy (DOE): Responsible for formulating and implementing policies for the energy sector.

- Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC): Regulates electricity rates and services.

- Generation Companies (GenCos): Includes both private companies and government-owned corporations that generate electricity. Examples include Aboitiz Power, San Miguel Corporation, and First Gen Corporation.

- Transmission Company:

- National Grid Corporation of the Philippines (NGCP): Operates the country’s transmission network.

- Distribution Utilities (DUs): Both private and public entities distribute electricity to consumers. Major players include Manila Electric Company (Meralco), which serves Metro Manila and neighboring areas, and various electric cooperatives covering other regions.

- Independent Power Producers (IPPs): These are private companies that generate electricity and sell it under contract to utilities.

- Retail Electricity Suppliers (RES): Under the Retail Competition and Open Access (RCOA) scheme, these suppliers sell electricity to the contestable market or larger consumers who have the option to choose their supplier.

- Consumers: Both residential and commercial users of electricity, who are increasingly becoming active participants with options like net metering for solar energy producers.

- Renewable Energy Developers: With the push for sustainable energy, companies focusing on renewable sources like solar, wind, and geothermal have become significant players.

Electricty generation and procurement

Additionally, the notice mandated that suppliers provide replacement power at the PSA rate or lower in all outage scenarios, including delays in initial delivery. This provision also stipulated that if replacement power incurred higher line rental costs than the original source, the excess would be charged to the supplier. Such terms add financial and operational risks, potentially deterring renewable energy providers from participating. These transparency limitations and challenging conditions highlight the need for accessible reporting and flexible terms in procurement to attract competitive and sustainable energy solutions in the region.

Conclusion

The Philippines is enthusiastically embracing an electric future, with the Electric Vehicle Industry Development Act (EVIDA) at the forefront of this shift. In 2023, the Department of Energy (DOE) established standards for EVs and charging stations, setting ambitious goals of deploying 300,000 electric vehicles and more than 7,000 charging stations across the country. The recent 2024 Philippine Electric Vehicle Summit, themed “Spark Change, Drive Electric,” reflected this momentum, showcasing innovations and igniting optimism about the nation’s transition to EVs.

However, beneath the excitement of the summit lies a pressing issue: in regions like Eastern Visayas, where electricity is both unreliable and expensive, the move to EVs may be premature. Many areas still rely on costly fossil fuels and endure frequent power interruptions, making EV charging a potential challenge rather than a solution. Without foundational changes—like ensuring stable, affordable electricity from renewable sources—the push for EV adoption may feel disconnected from reality for many Filipinos. While the vision for electrified transport is promising, it must be rooted in a reliable and sustainable energy infrastructure to make genuine progress.

Ideas and Solutions

Hosuehold-Level

What about solutions? On a private level, households in Region 8 that can afford it have long relied on diesel generators as a backup during extended blackouts. For inconsistent voltage issues, especially with delicate appliances like computers, many households use Automatic Voltage Regulators (AVRs). However, with the recent availability of affordable private solar setups, more households are beginning to consider solar installations as an alternative. For some, grid-connected solar is an option to reduce electricity costs, though it has limitations; during a brownout, these systems would still leave households in the dark. Additionally, in areas with highly volatile voltage, on-grid solar systems may struggle, as frequent fluctuations can prematurely wear down inverters constantly adjusting to the grid’s instability. In these cases, off-grid solar systems offer a more resilient option.

As battery prices have dropped, these off-grid setups now have a return on investment of roughly 3-5 years, depending on household energy consumption. They provide constant, reliable, and clean electricity, but remote areas face extra costs if installer companies need to travel from urban centers, and these setups are only feasible for structurally sound homes. Typhoon resilience is another consideration; systems need to be secured and safeguarded against extreme weather. Local knowledge also plays a critical role, as regular monitoring and maintenance are essential. Humidity and dust are significant concerns, making it important for users to understand upkeep practices to ensure lasting reliability of their solar systems.

Microgrids

For the majority of the population, installing a private off-grid solar system remains out of reach financially, often requiring a substantial loan. Here, municipalities and barangays have the power to bring change, and microgrids offer a promising solution. By implementing community-based energy sources, microgrids can address many of the region's energy challenges and, over time, reduce the maintenance demands of the large national grid.

Currently, projects like the "Solar-Safe Project," part of the “Strengthening Disaster Resilience and Risk Mitigation through Ecosystem-Based Planning and Adaptation” (E4DR Project), explore solar setups in evacuation centers. However, this approach has limitations; in many municipalities, evacuation centers are rarely used, often inadequately maintained, and lack essential facilities. Even during typhoons, many residents prefer to stay in their homes. A more practical focus would be to equip barangay halls, which are used daily and receive some level of maintenance. An even more impactful approach would be to install solar systems in schools. Schools serve as centers for learning and community activity, and with reliable electricity, students could study in a comfortable environment, free from heat and humidity. Schools in many countries double as evacuation centers due to their solid construction and suitability for housing people in emergencies. Improving Philippine schools to function as safe, resilient spaces would not only enhance education but also provide a dependable refuge in disasters.

In the long run, microgrids powering entire barangays could be a transformative solution, enabling communities to share energy resources. This aligns well with the Filipino culture of sharing and community support, offering a model of sustainable, collective energy independence. With trained local staff to maintain the systems, the excess energy generated could even be shared within the community, fostering resilience and reliability in times of need.

References

- The undervoltage limit is defined as 90% of the nominal voltage. The nominal voltage is to be assumed at 220V.

- The overvoltage limit is defined as 110% of the nominal voltage. The nominal voltage is to be assumed at 220V.